Four Quick Facts:

Date and Age: Saint Katharine Drexel died on 3 March 1955, at 96. This marked the end of a long life dedicated to service and faith.

Location: She passed away at St. Elizabeth’s Convent in Cornwells Heights, Bensalem Township, Pennsylvania, which served as the motherhouse for the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, the religious order she founded.

Health Decline: In the late 1930s, Katharine suffered a severe heart attack, which significantly limited her physical activities. For the last 20 years, she lived in quiet retirement, essentially bedridden, focusing on prayer and contemplation.

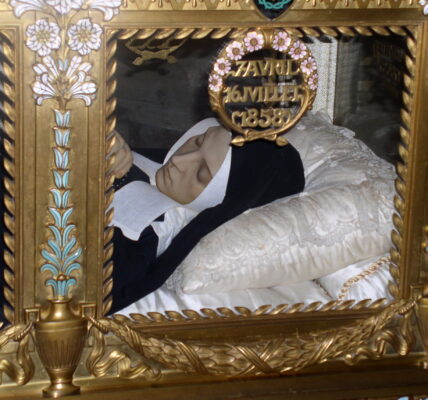

Burial and Legacy: She was initially buried in a crypt beneath the St. Elizabeth’s Convent chapel. Later, in 2018, her remains were transferred to the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul in Philadelphia, where they now rest at the Saint Katharine Drexel Shrine, reflecting her enduring impact as a saint canonized in 2000.

My religious background is not Christian. We did not attend a Christian Church or have any real Christian friends when I was growing up.

How did I become Catholic? I’ll briefly explain: As a reporter, I focused on faith and religion. I often covered events happening within the local Christian community where I lived.

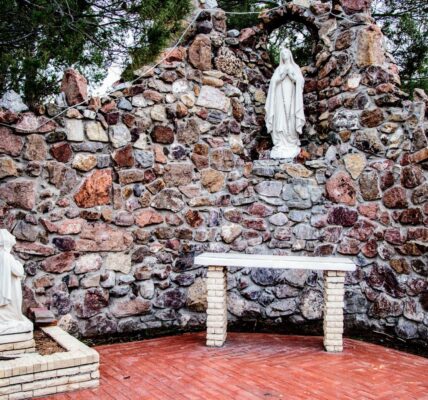

Over time, I began to focus on the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church in El Paso, Texas. While covering the Catholic Church, I began to feel a pull toward it.

That pull, tugging at my heart, led me deeper into the Church, where I learned about her teachings and why anyone would be Catholic. Then, two things pulled me in.

The first event was my being allowed to cover a Confirmation Mass at Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church in El Paso and hear Bishop Mark Seitz’s Homily. You can listen to that Homily by clicking here.

The next event was my covering the Christmas Mass at San Elizario Catholic Church in San Elizario, Texas.

After that Christmas Mass, I entered the RCIA. In October 2020, during COVID-19, I became a member of the Catholic Church.

Most of my family enjoys geology as a hobby. Everyone is interested in our past and history and wants to learn where we come from. We’ve discovered famous people, explorers, great schollers, and one Catholic Saint, Saint Katharine Mary Drexel.

Who was Saint Kathrine Mary Drexel?

Saint Kathrine Drexel is the second U.S.-born saint, and he was born on 26 November 1858 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her father, Francis Anthony Drexel, was a wealthy businessman and an associate of J.P. Morgan. Katharine’s mother, Hannah Jane Langstroth, died five weeks after Katharine was born.

Katharine, along with her sister, were taken care of by their uncle and aunt until 1860.

In 1860, her father married Emma Bouvier, who took great care of the girls and taught them the virtues of giving and helping the needy.

Katharine was born into wealth, her father being an international banker, and she wanted for nothing. Growing up, Katharine witnessed her stepmother welcoming the poor into her home three days each week, and her father spent half an hour in prayer nightly. This laid a foundation of prayer and charitable works in her life.

Katharine had an excellent education and traveled widely. As a rich girl, she also had a grand debut in society. All seemed well in her life until her stepmother became ill. For three years, Katharine cared for her stepmother until her death. Saint Katharine learned that all the money could not stop pain or keep people from death.

One thing Katharine and I have in common is a keen interest in the plight of the First Nations people. Katharine had been disgusted by what she read in Helen Hunt Jackson’s A Century of Dishonor.

Helen Hunt Jackson’s A Century of Dishonor, published in 1881, is a scathing critique of the United States government’s treatment of Native American tribes. The book meticulously documents the injustices inflicted upon Indigenous peoples over a century, focusing on broken treaties, forced removals, and systemic exploitation. Jackson highlights specific examples, such as the plight of the Cherokee, Cheyenne, and Sioux, to illustrate a pattern of dishonesty and moral failure in federal policies.

She argues that the U.S. government repeatedly violated its own agreements, displacing tribes from their lands and subjecting them to violence and poverty. The title reflects her central thesis: a hundred years of shameful conduct toward Native Americans, marked by greed and neglect. Written with a mix of historical analysis and impassioned advocacy, the book aimed to awaken public conscience and push for reform in Indian policy. It remains a landmark work in exposing the dark side of American expansionism.

While in Europe, Katharine met Pope Leo XIII and asked him to send more missionaries to Wyoming for her friend Bishop James O’Connor. The pope replied, “Why don’t you become a missionary?” His answer shocked her to consider new possibilities, maybe even a vocation.

Back home, Katharine visited the Dakotas, met the Sioux leader Red Cloud, and began her systematic aid to Indian missions.

Katharine Drexel could have married. But after much discussion with Bishop O’Connor, she wrote in 1889, “The feast of Saint Joseph brought me the grace to give the remainder of my life to the Indians and the Colored.” Newspaper headlines screamed, “Gives Up Seven Million!”

After three and a half years of training, Mother Drexel and her first band of nuns—Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored—opened a boarding school in Santa Fe. A string of foundations followed. By 1942, she had a system of black Catholic schools in 13 states, 40 mission centers, and 23 rural schools. Segregationists harassed her work, even burning a school in Pennsylvania. In all, she established 50 missions for Indians in 16 states.

Two saints met when Mother Drexel was advised by Mother Cabrini about the “politics” of getting her order’s Rule approved in Rome. Her crowning achievement was founding Xavier University in New Orleans, the first Catholic university in the United States for African Americans.

At 77, Mother Drexel, like many in our family, suffered a heart attack and was forced to retire. She felt her life was over. For the next twenty years, she prayed from a small room overlooking the sanctuary of a Church. At age 96, Saint Kathrine Mary Drexel died. She was canonized in 2000.

It’s comforting to know that I can turn to a family member, Saint Kathrine Mary Drexel, to intercede for me on my behalf.

Prayer to Saint Drexel:

Saint Katharine Drexel, you who saw the needs of the marginalized and dedicated your life to serving God’s people, especially the Black and Native American communities, pray for us. Inspire us to follow your example of selfless service and to work for justice and equality. May we, like you, be instruments of God’s love and compassion, always seeking to meet the needs of those in greatest need. Saint Katharine Drexel, pray for us!